Greek Women in Ancient Greece

Ancient Greek women’s lives intertwined with various aspects -marriage, family life, religion, education, intellectual life, and the harsh existence of servitude. The complexity and diversity of the Greek female experience emerge as a narrative that transcends linear categorization, interwoven with the threads of societal norms, institutional structures, and socio-political dynamics.

Marriage and Family Life of Ancient Greek Women

Marriage and Family Life in Ancient Greece

The dynamics of marriage and family hold a significant place in the history of human civilization and have evolved expansively over ages. One of the foundational civilizations, ancient Greece, endeavored a distinctive approach to family life and marital regulations, portrayals absent in the contemporary world.

In the realm of matrimonial conducts, the understanding of ‘marriage’ as perceived by the ancient Greeks differs vastly from today’s interpretation. Typically, marriages were not an expression of love or mutual consent, but a strategic familial alliance seeking to enhance social status, wealth, or lineage preservation. Consequently, marital unions were often arranged by the parents or dominant male figures within the family.

The ‘Ekdosis,’ a formal procedure of giving away, constituted a quintessential part of the marriage process. During this ceremony, the father or guardian would present the bride-to-be to the future husband. The exchange of dowry, objects or wealth given to the groom by the bride’s family, often followed this. This practice showcased the stark patriarchal structure that dominated ancient Greek society, where women essentially transitioned from the ownership of one man to another.

A significant notion to acknowledge is the absence of ‘marriage age’ guidelines, often leading to unions between adult men and adolescent girls. The primary function of the wife was relegated to procreation, specifically the production of legitimate male heirs necessary for preserving family lineage.

Turning to family life, the ancient Greek family or ‘Oikos’ was not just considered a kindred unit but also an economical and political entity. The head of the Oikos, usually the eldest male, had absolute power concerning internal issues like property, marriage, and even determining the fate of newborns.

Pertaining to the role of women within the Oikos, they were confined firmly to the private sphere. Women bore the responsibility of household management, domestic labor, and child-rearing. Surprisingly, Spartan society offered a semi-exception where women were given a certain degree of freedom, including property rights and physical training, but even here, they remained largely subordinate.

The offspring, in many instances, embraced a gender-biased upbringing. Male children received education and military training, preparing them for citizenship and warfare. Contrastingly, female children were typically primed for matrimonial roles, gleaning their knowledge from mothers and attending to domestic tasks.

This brief exploration into ancient Greek marital and family regulations grants a significant insight into a civilization’s earlier approaches to social structures. The understanding informs contemporary societies, illuminating our socio-cultural evolution, enabling us to appreciate the progress we have made, while still acknowledging the vast expanses yet to be traversed. Indeed, the study of ancient traditions elucidates history’s value, captivating not just scholars, but any individual seeking a deeper understanding of the human narrative.

Religious Roles of Women in Ancient Greece

Despite the confinement of women to the home and their perceived subservience within the patriarchal structure, they played vital roles in the religious life of ancient Greece, an often-underestimated facet of their societal involvement. Fortifying our comprehension of these religious responsibilities provides a broader perspective on ancient Greek women’s influence than merely viewing them through the domestic lens.

Iconographic Collections

The pantheon of Greek gods and goddesses included deities associated with women’s lives and societal roles, revealing an ingrained recognition of women’s importance in the spiritual realm. For instance, Hera was the queen of the gods and protector of women, particularly in childbirth, while Athena was the goddess of wisdom and warfare, and Artemis, the goddess of the hunt and virginity.

Ancient Greek women were pivotal participants in religious activities, often leading roles in rituals and ceremonies, that were integral to the smooth functioning of society. From acts like tending familial shrines to participation in state religious festivals such as the Dionysia and Panathenaia, they performed their duties diligently.

In the Athenian festival of the Thesmophoria, the most significant religious ceremony reserved only for women, they played integral roles. Dedicated to the goddess Demeter, this festival was a communal celebration of fertility and the agricultural cycle, underscoring the importance of women in nurturing and preserving life.

Peculiar to Sparta was the festival of the Hyacinthia, where Spartan girls and boys participated equally, dancing and singing hymns in honor of the slain prince Hyacinthus, defying the otherwise prevalent segregation of genders in most ancient Greek religious ceremonies.

Priestess roles were highly esteemed in ancient Greece, frequently reserved for aristocratic or royal women, contributing another avenue for women’s societal contributions. Priestesses, such as the Oracle of Delphi or Priestess of Athena in Athens, wielded significant social influence, especially despite conventional gender hierarchy, delivering divine prophecies or sanctified wisdom that could dictate state policies and decisions.

Also, vestal virgins had profound roles, preserving the sacred fire of Hestia, the goddess of hearth and family, a duty believed crucial for the city-state’s welfare. By taking vows of chastity, these women could sidestep the usual restrictions of marriage, living under the condition of absolute purity while conducting sacred rites and prayers.

Therefore, while academic emphasis has often been on women’s familial and domestic roles in ancient Greece, their religious roles bore profound significance that unquestionably influenced societal dynamics. Recognizing these responsibilities and their impacts extends our appreciation for women’s roles in this world, where their input was hitherto considered limited and relegated to a private sphere.

Women’s Education and Intellectual Life in Ancient Greece

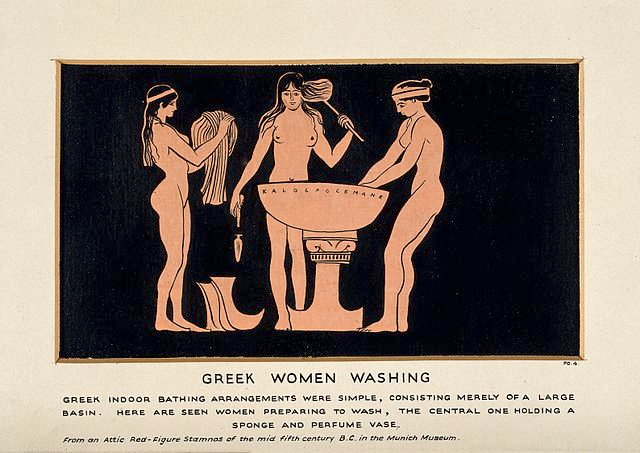

Delving now into the sphere of education and intellectual pursuits, the status of women in ancient Greece continues to provide fascinating perspectives on gender roles in that era. For the majority of ancient Greek city-states, women’s education was primarily focused on household and matrimonial responsibilities. Girls were taught skills necessary to run the oikos, including weaving, cooking, and other forms of domestic work.

Ancient Greece, however, did harbor noteworthy exceptions to widespread restrictions on female education. The gender-equal society of Sparta, for instance, insisted on physical training and education for both boys and girls. Girls participated in sports like wrestling, discus, and gymnastics, unveiling a panorama of potential female vigor far beyond the boundaries set by other Greek city-states. The idea behind this unusual social practice was to generate healthy women who could bear strong Spartan warriors, underlining a notion of utility even in apparent gender equality.

In the midst of confinement to the private sphere, some Greek women managed to cross the threshold of intellectual life. The Pythagorean philosopher, Theano, famously known as the wife and student of Pythagoras, is celebrated for her noteworthy contributions to mathematics and philosophy. Her works – fragments of which survive today – testify to a rare prominence of female intellect in ancient Greece.

Similarly, Home Economics (Oikonomike) by Xenophon offers an interesting glimpse at the potential intellectual capacity of Greek women. His characterization of a wife as the manager of household affairs implicitly acknowledges a woman’s capacity for strategic thinking and decision-making, hinting at a nuanced understanding of a woman’s role beyond just procreation and household chores.

The great tragedy poet Euripides also portrayed his female characters as intelligent, cunning, and eloquent, often surpassing their male counterparts. His plays highlight the potential for intelligence and wit among women even in a society where they were largely secluded from intellectual pursuits.

The preserved poetic works of Sappho, from the island of Lesbos, further illuminate the intellectual caliber of women in ancient Greece. Her lyrical poems, centered around themes of love and passion, continue to resonate with audiences today, revealing the emotional depths and intellectual faculties of women of her time.

Despite substantial hindrances, the intellectual realm was not entirely beyond the reach of women in ancient Greece. Considered as one society at one point in history, ancient Greece honed vivid illustrations of gender dynamics that simultaneously confined and transcended women beyond their traditional roles. A look at the past always provides valuable insights into the course of social evolution. Thus, understanding the intellectual lives of women in ancient Greece may help broadify our understanding of gender constructs and societal norms not only in the historical context, but also in their modern implications and transformations.

Servitude and Slavery Affecting Women in Ancient Greece

In deepening our exploration of women’s lives in ancient Greece, it becomes necessary to peer into the shadows of slavery and servitude. Arguably, these fundamentally structured the existence of thousands of women, painting a stark image of the life cycle of women severely contrasted to the married citizen women.

Primarily, servitude and slavery represented an inescapable life station for both indigenous and foreign women. Women could be born into slavery if their mothers were enslaved or targeted as war captives. Infamously, such was the case with the thousands of women captured during the Peloponnesian War. These captive women were intrinsically linked to a life of labor and servitude.

The duties of these enslaved women were starkly different from citizen women, whose primary focus was the oikos. Enslaved women were often responsible for the strenuous labor both within the household and in the agrarian fields. Their tasks in the household included cooking, cleaning, spinning, weaving, and nursing, while in the fields, they performed intense physical labor. In essence, their life was inextricably tied to strenuous physical labor, something the citizen women had little exposure to.

Yet, even within the confines of slavery, there were certain roles, such as that of the ‘choregoi,’ which were somewhat esteemed. These women, often enslaved and owned by wealthy men, were trained in music and dance and employed to entertain guests during symposiums. Notably, these women held a certain societal recognition, though still bound by the chains of their enslaved status.

The role of concubines, or ‘pallakai,’ is another crucial piece of the puzzle in grasping the full scope of women’s lives in ancient Greece, and how it was shaped by servitude and slavery. Notably, these women held a position somewhere between a wife and a slave, neither fully free nor entirely enslaved. They were considered ‘partners’ rather than lawfully wedded wives, where their primary role was to bear children for their master. The children born out of these unions, while not viewed as legitimate as those born to citizen wives, were not considered slaves either.

The existence of concubines was largely driven by the need for heirs, particularly in situations where a citizen wife was unable to bear children. This presented a distinct differentiation in the roles of women in ancient Greece, where the legislation of women’s bodies served the strategic purpose of furthering familial lineage.

Lastly, the study of religious slavery provides an insightful perspective, especially in the extensive instances of temple slavery. These women, albeit enslaved, held crucial roles in many religious ceremonies and rituals, similar to the priestesses and prophetesses. Uniquely, their enslavement was regarded as servitude to not only humans but the gods themselves, and their role in prophecies and religious ceremonies lent them an elevated stature.

Delving into the realm of servitude and slavery representative of the lives of numerous women in ancient Greece unlocks a vast, and often overlooked, perspective. This deepens our understanding of the complex societal structure that these women navigated in their daily lives, illuminating the intricacies of ancient Greek society. It is a vivid testament to the multifaceted and often harsh existence of women beyond the citadel walls, shaping the historical narrative of ancient Greek culture, values, and societal norms. Even so, it offers an understanding of the resilience of women who deftly navigated these circumstances, their stories shining through the lens of history.

The expanse of roles held by women in ancient Greek society paints a captivating canvas of valor and struggle, triumphs and challenges. The rich tapestry of their lives defined the essence of a civilization known for its philosophical, artistic, and intellectual contributions to humanity. Their position within the familial structure, their religious roles, their participation in intellectual life, and their experiences of servitude and slavery brings out a narrative that continues to echo throughout the corridors of time. Exploring these facets of ancient Greek women’s roles provides a nuanced understanding of their standing in that era, further enriching our perspective on the evolution of women’s roles in societies worldwide.